The Quiet Thread

Issue No. 04 – When the meadow falls quiet

Stories from our home at 682.5 metres above sea level

A meadow is never truly finished — only resting until the next season. Ours has taught us patience, rhythm, and the quiet joy of trying again.

Rocks, bricks, and exhaustion

The story of our flower meadow really began on the other side of the house, with a very different project. For ten years we built a stone garden. There were the enormous rocks from the forest that absolutely had to be rolled home, no matter how far or how heavy, and the endless piles of recycled bricks collected from all over the county because paving seemed like such a good idea at the time. By the end of it we were proud, sore, and completely exhausted.

So we thought: now let’s make it easy. A flower meadow. Just scatter some seeds, sit back, and enjoy. How hard could it be?

Arne’s Childhood meadows

Arne remembers summers at Mjødoksetra in Vestfjell, where he stayed with his siblings and grandparents. There was a perfect flower meadow there that seemed to come entirely by itself. In autumn the grass was cut, and if not, the cows grazed it down. Their hooves pressed the seeds into the soil, and the flowers returned the following summer without fail. That effortless cycle was, for him, the picture of what a meadow should be.

Inspired by a king

Later we saw King Charles’ meadow at Highgrove — a glorious, painterly field of wildflowers buzzing with life. It looked simple, achievable, something we could surely copy. Four bags of seed came home with us from the gift shop, scattered straight onto the grass with all the confidence in the world. By next summer, we imagined, we would be sitting in our own sea of flowers.

Failure and research

Next summer came, and not a single flower appeared. Not one. All we had was grass, thick and healthy, smothering every chance of bloom. That was the moment we discovered that a flower meadow is not the easy option after all.

So began our research phase — which for us meant ordering every book we could find. Page after page we studied, trying to make sense of it all. A meadow is not just a field of flowers. It is a finely tuned ecosystem. You need poor soil, not rich. Timing. Patience. Cutting, leaving, raking, shaking, removing. We soon realised we were in far deeper than we had ever expected.

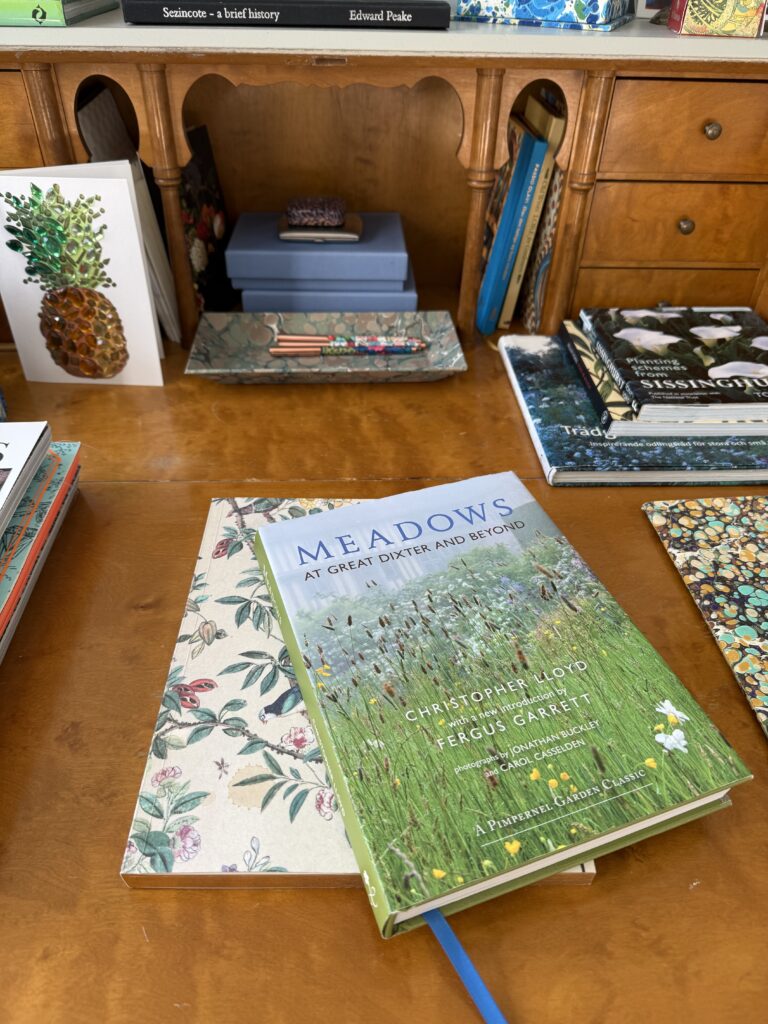

One of our favourite meadow books on Carlos’ desk. See the end for a close-up. Photo © ARNE & CARLOS

We even went back to Highgrove, this time through the online shop. When the package arrived, it included a printed note from the King (who was the Prince of Wales at the time) thanking us for supporting his foundation. Carlos joked that Charles and Camilla must be in the warehouse themselves, packing up orders: “Right, Camilla, here’s one for Arne and Carlos, let’s get it packed and sent off.” Of course the letter wasn’t personal, but it felt almost as if it were — and that was funny enough.

Lessons from yellow rattle

Along the way we discovered one of the meadow’s quiet secrets: yellow rattle (Rhinanthus minor). A modest little flower, parasitic on grass roots, it opens space for other wildflowers to grow. Without it, the grass wins every time. With it, the meadow has a chance. Ever since, we’ve been trying to establish it here — scattering and hoping.

So when the first yellow flowers appeared, it felt like we had won the lottery. Finally, yellow rattle! Unfortunately, Arne’s plant app confirmed otherwise. What we had was bird’s-foot trefoil — lovely in its own right, but not the miracle worker we were hoping for. We are eternal optimists, though, and one day yellow rattle will arrive. We’ve even set aside a bottle of champagne for that day.

Not quite the yellow rattle we hoped for, but bird’s-foot trefoil will do for now. Photo © ARNE & CARLOS

Our patches today

Now we are working on two patches of meadow: one by the old storehouse that will one day be our studio, and another that slopes gently down towards the water. The patch by the water has come furthest; the one by the wall is still stubborn. Every summer means clearing shrubs and raspberry canes, pulling out saplings, cutting with the scythe, digging with the spade and crowbar. We rake, we stamp, we sow. Slowly, slowly, things improve. Not perfect — not even close — but better than before.

Talking with the royal gardeners

Each summer, when we return to Highgrove or visit other English gardens like Great Dixter, we look at their meadows and realise just how out of our depth we are. At Highgrove, the gardeners explained their method: let the flowers bloom, cut them down at the end of the season, leave the cuttings to dry and shed their seeds, then finally clear them away. After that, in come the sheep. They graze, they trample, they press the seeds into the soil. It is, apparently, the proper way to do it. Which means that one day, if we are serious, we may also need to add a couple of sheep to our household.

We have started to cut down the meadow. Now, where do we find a couple of sheep? Photo © ARNE & CARLOS

Joy in imperfection

For now, though, we make do with our imperfect version. Even if it is far from perfect, it is wild. Flowers do appear — not in great abundance, but enough to make us smile. And that is something. We have learned that perfection is not the point. The joy is in watching what comes, in seeing the bees and butterflies, in noticing a flower appear in a place where yesterday there was none.

Perhaps one day we will manage the meadow of our dreams. Until then, we take delight in the imperfect one we have — and in the fact that even mistakes can be beautiful. And as with everything else in our lives, the meadow has found its way into our work. We are already sketching and knitting, letting ourselves be inspired by the shapes and colours of wildflowers. Not necessarily from our own meadow, but from meadows in general — that sense of abundance and surprise, of life springing up where it will.

So don’t be surprised if one day you find yourself knitting flowers that were first imagined in a very imperfect meadow, halfway up a mountain, where two people are still learning, still laughing, and still dreaming of getting it right.

Click here for our knit and crochet patterns inspired by our meadow.

Gunnhild, our very first project inspired by a flower meadow, designed in 2012. Click the photo for the pattern. Photo: Ragnar Hartvig © ARNE & CARLOS

Meadows at Great Dixter and Beyond, by Christopher Lloyd and Fergus Garrett — horticulture at its best. Photo © ARNE & CARLOS

Skip to comment form

I appreciate the comments I read here. I, too, enjoy reading your stories and reflections. They are refreshing, inspiring, and relaxing. I look forward to reading more and can’t wait for the new six-rows-a-day project.

I enjoy reading your letters! I especially enjoy them because I have many of the same interests as you two do! The adventures of gardening this time was especially interesting and joyful reading! Thank you for the time and effort that you put into bringing these to us!

How wonderful the see and hear about your pursuit and accomplishment of a meadow. As beautiful it is I for one never realized it’s such a difficult thing to accomplish. I don’t have acreage but if I did a meadow would be ideal. I would love it. We once were stationed at Ft Leavenworth, KS right next to Kansas City, MO(my home town❤️) The landscape is not flat there as most I’m sure imagine Kansas is. The rolling hills are beautiful and slope to the river dividing the two Kansas Cities, Kansas City, KS and Kansas City, MO. The first place we lived on the Missouri side in a town named Platte City. The field behind of our rental was a meadow. I always imagined it as a vineyard for some reason. Best luck with everything coming up I look forward to reading more and seeing y’all on Sit & Knit for a Bit. Can’t wait for the surprise coming our way.

So very lovely! Your story about the garden is an inspiration, the photos are amazing. Reading the blog reminds me of books I’ve loved that draw you in to another world, a world that is wonderfully colorful and hopeful. Many thanks.

wow you both have such a beautiful Souls Loved reading this and your meadow will be beautiful …it already is xx

I love reading about your meadow! I’m trying to integrate what I call a Prairie Garden into my landscape, similar to your wildflower meadow. I’m smack in the middle of the US where prairies used to roll for miles. I appreciate you two giving me a bit of peace and joy through sharing your lives!!

Your story is inspiring. Your work and stories are wonderful to see and read, and made me feel very emotional. Keep up with all that you do. s

Sending much ❤️ love.

What a beautiful story and your gardens are lovely. Thanks for sharing

This is a beautiful piece, I loved reading it. my meadow is tiny and over run with weeds, but I’ll continue to try and make it beautiful.

Sounds like a wonderful project. I think the sheep might be leaving some fertilizer too 🙂

What an inspiring realization: imperfection is beautiful. 🌻 Each day your “imperfect” meadow brings you the small gift of a new little flower.

Not imperfect at all! Just what it needs to be; thank you for your gracious acceptance. 💜

Since I live in Alaska at about the same latitude as you two, I find your garden pursuits so relevant. In addition to our vegetable/flower gardens and potato patch, we have been planting a buckwheat patch in the front yard. We have been enjoying it for a few years, replanting each year, and it leaves us with resilient tall white blooms. It has been fun.

Hi Guys. I really like this new gentler, more contemplative version of yourselves. It is a nice space to hang out in. Your lives seem so supercharged and leave me feeling…”less”…because I’m not doing as much. I know, “compare, despair.” Your big home life and all your travels are quite amazing and inspirational. So I enjoy these glimpses into the softer, slower moments of your lives. Carry on, and big love from Chicago!

My wildflower meadow is prolific in its first season. I planted annual and perennial seeds. And yes, I believe poor soil is key. I know the day is coming I will have to cut it all down. I am curious about how it will look in the winter. And excited for next spring

Our wildflower meadow journey seems to be starting out the same way yours had LOL!! Definitely adding this book to our wishlist! Thanks for sharing your story and pics. <3